My 911 memory: On a train with strangers

A Story That Requires No Words

September 3, 2016

Book covers from another era

November 12, 2016My 911 memory: On a train with strangers

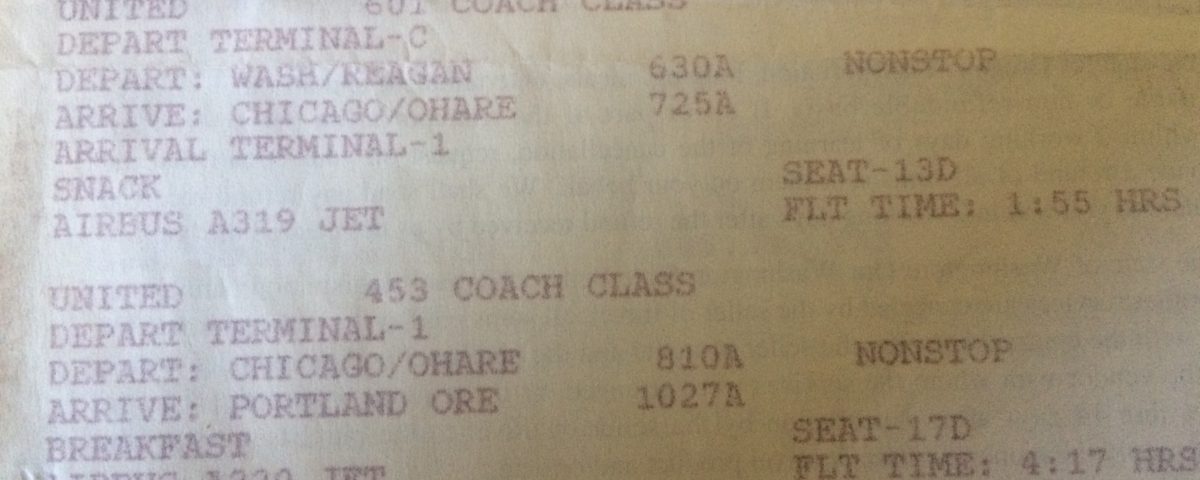

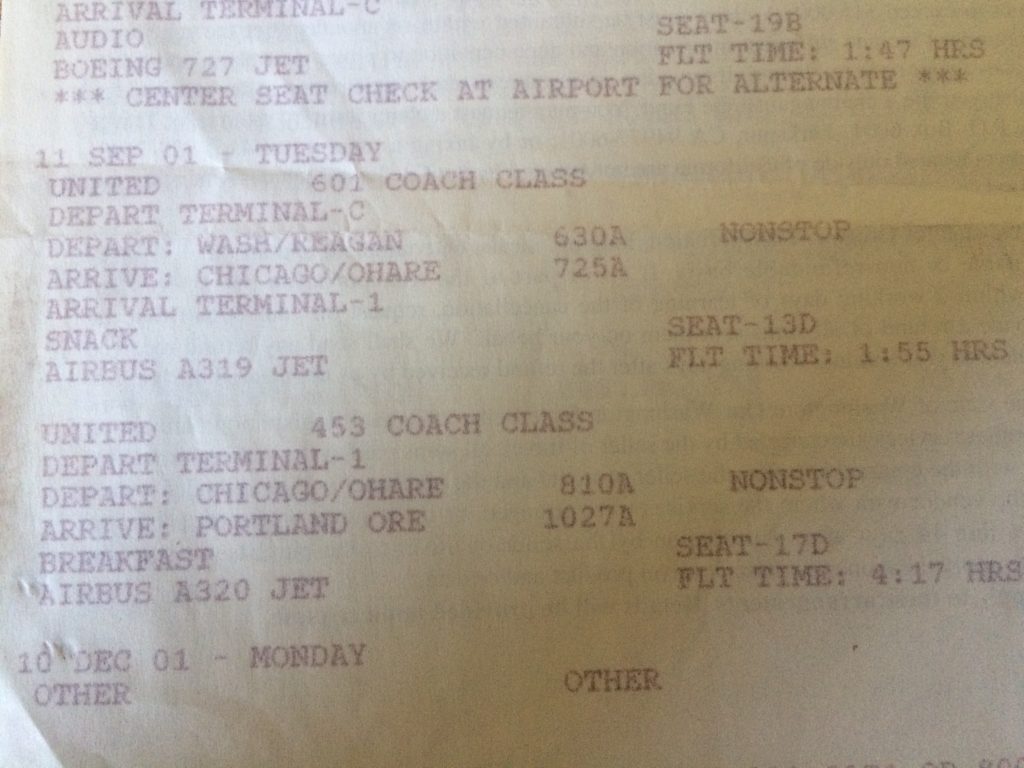

When the United States was attacked on September 11, 2001, I was on a United Airlines jet heading west.

When the United States was attacked on September 11, 2001, I was on a United Airlines jet heading west.

Earlier in the morning, I’d taken off from Washington, D.C. where I’d been part of a panel of journalists speaking about the Pulitzer Prize.

I wanted to write about my experience that day. But people at the paper told me, 15 years ago, that it wasn’t a story.

So I filed it away.

But it now seems appropriate to share it.

We took off from Chicago, and about 20 minutes into the flight, the pilot came on the intercom:

“For passengers, who notice these things, you will see that the sun is now on the left side of the plane. We’re heading back to O’Hare.”

We had no idea what was going on. Passengers started to grumble about delays and missed connections. When the plane landed at O’Hare, we looked out the windows and saw the runways were packed with planes. The pilot told us we were being directed to a spot far from the terminal until a gate opened.

Rumors started sweeping through the cabin. Someone whispered there must be a bomb on our plane.

The panic was palpable.

A passenger a few rows behind me, got on the airline phone, called home to talk with his wife, telling her he’d be late. He called out to us minutes later to say there were reports that a plane had slammed into the World Trade Center.

The pilot found us a gate.

The terminal was pandemonium. Thousands of people jammed the hallways.

All the television stations had been turned off. But I heard snatches of conversations: World Trade Center, terrorism, and that the nation’s nonemergency civilian planes were grounded.

I knew I’d be stuck for a while in the airport.

I travel light.

I grabbed my bag, and ran to the Hilton Hotel on the airport property.

I asked if they had a room.

I got the last one.

I checked in, got upstairs and called him. I told my family I was safe. I turned on the TV to see what was going on.

Then I went down to the hotel bar.

It was packed.

I shared a table with pilots from American and United airlines. They bought me a drink, and then bought a round. We watched the TV reports. They told me they knew the pilots who had died in NYC, Pennsylvania and at the Pentagon.

I remember one of the pilots crying, and another pilot wrapping his arm around the man’s shoulders.

I spent three days in an airport hotel – in the bar, talking and listening — before I boarded a train to Portland.

So many people were heading west that Amtrak added extra cars. I got a window seat and wondered who’d share a seat next to me. Finally, we settled in, ignoring one another in the way strangers segregate on an office elevator.

This was in an era before the IPhone, so we were in a bubble. No one knew what was happening in the rest of the world. At stops along the way, someone would get out, buy a newspaper and then come back to report to the car what was going on.

Then, only because we were strangers, we let down our guard. The dining car was packed, and we had to share tables.

We learned about each other.

Not just facts – our names, where we lived and what we did for work – but how we lived.

Because we knew we’d never see each other again, we felt free to ask probing, almost intrusive questions that none of us would have asked in any other situation.

We learned about the man battling booze, the woman worried about her children, and the salesman growing old, fearful that he wasn’t going to make his monthly figures.

So those are my 911 memories: Spending nearly 40 hours on a train, crossing the country with fellow travelers, all of us wondering where we were headed.

I never saw those people again.

And yet they linger in my soul.